Kathrine Switzer: A Celebration Of Women In Running

“I wasn’t running Boston to prove anything, I was just a kid who wanted to run her first marathon.”

American marathon runner Kathrine Switzer (born on January 5, 1947 in Amberg, Germany) never intended to change the world – all she wanted to do was run.

But it was this passion for running that led her to competing in the male-only Boston Marathon on April 19, 1967 – an era when women were considered too ‘fragile’ to race – not to mention that running was perceived as ‘unfeminine’ or even detrimental to a woman’s fertility.

Kathrine wasn’t trying to be a champion of her time, or even to disprove the common myth that women weren’t strong enough to race. She simply ran for the love of it, and yet the race would change her life and be a catalyst for positive social change – paving the way for women in sport for future generations.

Today we’re celebrating International Women’s Day and the achievements of women across the globe – not only in sport, but in evolving social perceptions, challenging gender stereotypes and spearheading positive change - to embrace equity in all aspects of society and culture.

Together, we can nurture a world where equity is the norm, not the exception, where all girls and women have the encouragement, support and opportunity to be included and to be heard.

Kathrine Switzer’s journey is a remarkable example of how one woman changed the world – but each of us can make a difference. Be inspired by Kathrine's story, but also be self-inspired by celebrating diversity and the achievements of the women in your life.

Kathrine’s Switzer’s Introduction To Sport

Kathrine Switzer was born in 1947 to an American military family stationed in Germany, and 2 years after her birth they returned to the United States.

Running was a critical part of Kathrine’s life from the age of 12 years old and as a teenager living in Fairfax County, Virginia, Kathrine embraced the positive physical and mental benefits of sport. Her father encouraged her to join the field hockey team at high school and to run a mile a day to surpass the performance of her teammates. This daily routine gave her a sense of victory – her peers may be bigger than she was – but she could run.

She embraced the freedom and empowerment running provided and sought out ways to get more involved in the sport. During her studies at Lynchburg College, she participated in the limited short-distance track events that were accessible to female athletes. She transferred to Syracuse University to study journalism with ambitions to be a sports writer, but despite the university offering a plethora of sports for men, she discovered there were no opportunities for women.

Rather than letting this be a barrier to her running pursuits, she trained unofficially alongside the men’s cross-country team, supported by coach and veteran Boston marathon runner Arnie Briggs.

One Dream & A World Of Change For Gender Equality

Kathrine loved hearing her coach’s inspiring stories of the Boston Marathon, but she wanted more than that. She wanted to live it.

“I snapped and said, ‘Oh, let’s quit talking about the Boston Marathon and run the damn thing!’”

It was December 1966 and Kathrine and Briggs were running in a “wild snowstorm” – evidence of her resilience. However, Briggs remained sceptical of her abilities to conquer the epic 26.2 mile (42.195km) marathon distance, sparking a heated argument with the man that under usual circumstances she viewed as her “kindly old coach”.

According to Kathrine’s memoir, Marathon Woman, “Arnie insisted the distance was too long for fragile women to run and exploded when I said that Roberta Gibb had jumped into the race and finished it the previous April.”

Even after his insistence that “'No dame ever ran the Boston Marathon!'” eventually she persuaded Briggs, remembering his words;

“'If any woman could do it, you could, but you would have to prove it to me. If you ran the distance in practice, I’d be the first to take you to Boston.'”

Now she had a dream, a coach, and the ambition to succeed. If Kathrine successfully trained for the distance, Briggs would not only support her goal to run in the Boston Marathon, but would run by her side.

The Lead Up To The 1967 Boston Marathon

After months of training and with only 3 weeks to go until the Boston Marathon, Kathrine and Briggs did a trial run of 26 miles (about 42km) which “felt too easy”, so on Kathrine’s insistence Briggs reluctantly agreed to commit to another 5 miles (8km). While Briggs “passed out cold” by the end of it, Kathrine’s mood was a stark contrast, "I hugged him ecstatically". She had proven she was capable of running a full marathon and more.

20 year old Kathrine registered for the race the next day, paying the entry fee and signing the mail-in entry with her initials ‘K. V. Switzer’- her standard signature which would also avoid bringing attention to her gender. Briggs insisted that if she was going to race, she’d have to do it right and officially – just like any other runner. Technically this was permitted, as there was no official rule that said women couldn’t compete… and yet it was unheard of, as the social misconceptions of the time misled women to believe they weren’t physically able.

2 weeks later Kathrine discovered her boyfriend at the time, ‘Big Tom’ Miller, an American football player and John Leonard, a member of the university cross-country team would join Briggs and herself in running the Boston Marathon.

Kathrine’s support network was complete – but her boyfriend’s motivation was impulsive and demoralising, “If a girl can run a marathon, I can run a marathon” – and he insisted on doing so without any training.

The Day Before The 1967 Boston Marathon

After a five-hour drive to Boston with her running team in tow, Briggs drove the marathon route, pointing out landmarks with enthusiasm through the bitterly cold air and rain-covered windows at 10pm at night. For Kathrine this was a seemingly endless and disheartening look at what was ahead.

“The drive seemed an eternity, and I had this impending feeling of doom—here we were driving at 40 miles an hour and it was taking forever. Ever since that night I’ve never driven over a marathon course before the event. It is totally demoralising to see how far 26 miles actually is.”

When arriving at her hotel room with her confidence shaken, she called her parents.

“My dad was acutely aware when it came to any anxiety on my part; I never reached out with a lack of confidence unless it was serious. And he delivered perfectly. ‘Aw hell, kid, you can do it. You’re tough, you’ve trained, you’ll do great!’”

That gave her reassurance and fuelled her motivation, but naturally, she still had fears that the unexpected could steer her off track.

“What I couldn’t explain to him, what nobody knows unless they’ve done one, is that the marathon is unpredictable, anything weird could happen, and anything could happen to me!... Eventually, I got too tired to worry about things I could not control. The thing I worried about most was courage. Would I have the courage to keep running if it really hurt, if it got harder than I was used to, if Heartbreak Hill broke me?”

The Day Of The 1967 Boston Marathon

Kathrine respected the legacy the Boston Marathon represented, being held on Patriots’ Day. It was a day that honoured the key role of the Battle of Lexington and Concord to American history, being the foundations of American independence from the British.

“I thought it was neat that folks in Massachusetts got a special holiday commemorating the young American patriots who fought the British in the first battles of the American Revolution.”

On Wednesday, April 19, 1967, another layer of history would be added to the Boston Marathon – and unknown to Kathrine Switzer, she would be at the heart of it.

The weather was brutal and unforgiving however the snow and punishing rain didn’t shake Kathrine’s resolve – she had trained for this.

“The Boston Marathon started at noon, a great gift, as we slept in and didn’t eat breakfast until 9. Arnie said to chow down; we needed a lot of fuel because it was a long day and cold outside. He wasn’t kidding—it was freezing rain, with sleet and wind. So we ate everything: bacon, eggs, pancakes, juice, coffee, milk, extra toast. Oddly, the weather didn’t concern me; we’d trained five months in weather like this.”

They joined the mass of runners, with 741 people registered to compete. Like any other competitor, Kathrine was assigned a race number – 261 – a number that would be remembered in history as an inspiring symbol of the women’s rights movement. The number was pinned to her sweatshirt, an old friend that she had worn for many strenuous yet worthwhile hours of training.

“I pinned my numbers on my sweatshirt and not my burgundy top. It was the final commitment to wearing that warm sweatshirt for the whole race. I was pleased; the sweatshirt had been a buddy in Syracuse for several hundred miles and would live on another day, rather than dying at the roadside on the way to Boston.”

Kathrine’s presence startled many runners out of their focus during pre-race warmups – yet the response was overwhelmingly positive and welcoming.

“As runners jogged past, most kept their nervous eyes ahead, lost in prerace concentration, but plenty did double takes, and when they did I’d smile back or wave a little wave. Yep, I’m a girl, my look back said.”

She recalls their delight, “’Gosh, it’s great to see a girl here!’” and “’Can you give me some tips to get my wife to run? She’d love it if I can just get her started.’”

Runners were shepherded to the starting line in a disorganised mob by the Boston Athletic Association officials, who were ticking off bib numbers. In the chaos Kathrine didn’t stand out as being out of place – she was a runner among runners.

The starting gun went off and she was racing – finally a part of the pilgrimage runners had been participating in for 70 years – the Boston Marathon. All the months of training and anticipation had led to this. As she moved one leg in front of the other, she felt truly in her element in a way that no other race could compare.

“After months of training with Arnie and dreaming about this, here we were, streaming alongside the village common and onto the downhill of Route 135 with hundreds of our most intimate companions, all unknown, but all of whom understood what this meant and had worked hard to get here. More than ever before at a running event, I felt at home.”

She was elated with the storm of excitement from both racers and crowd. There would be future pain as her legs would fatigue and her mental resilience would be tested, however now was the time to soak in the joyous encouragement around her.

“The first few miles of every marathon are fun. The running is easy, the crowd noise is exciting, and your companions are conversational and affable. You know it’s going to hurt later, so you just enjoy this time.”

Shortly into the race, she had unwittingly gained the attention of the press truck who were in awe of a woman wearing race numbers. Photographers snapped pictures of Kathrine and her team, however the mood was of excitement – not disgust or agitation that a woman would join a race that was ‘for men’.

Breaking her out of the joy of laughing and waving, Kathrine was startled by a noise that sounded unnatural in a sea of runners.

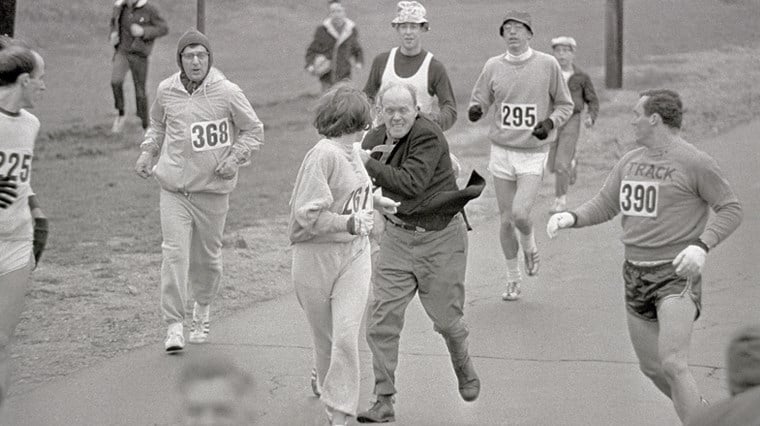

“I heard the scraping noise of leather shoes coming up fast behind me, an alien and alarming sound amid the muted thump thumping of rubber-soled running shoes. When a runner hears that kind of noise, it’s usually danger… Instinctively I jerked my head around quickly and looked square into the most vicious face I’d ever seen.”

“’Get the hell out of my race and give me those numbers!’” – she recalls the aggressive words of race director Jock Semple as he grabbed at her sweatshirt and clawed at her bib number.

“The bottom was dropping out of my stomach; I had never felt such embarrassment and fear… the physical power and swiftness of the attack stunned me. I felt unable to flee, like I was rooted there.”

Her boyfriend at the time 'Big Tom' Miller sprung to her aid, cross-body blocking Semple and slamming him out of reach of Kathrine. "There was a thud—whoomph!—and Jock was airborne. He landed on the roadside like a pile of wrinkled clothes."

With Brigg’s shout of “Run like hell!” the team pushed forward, fuelled by a rush of adrenaline. Kathrine was physically and emotionally shaken by the experience.

“I was dazed and confused. I’d never been up close to physical violence; the power was terrifying and I was shocked at how helpless I, as a strong woman, felt against it.”

The images captured by the press in those heart-racing moments would be among the most iconic photographs in history, a snapshot of the struggle for gender equality.

Alongside fear, doubt too begun to take hold, but Kathrine brushed it away, instead channelling her anger into determination;

“… for just a tiny moment, I wondered if I should step off the course. I did not want to mess up this prestigious race. But the thought was only a flicker. I knew if I quit, nobody would ever believe that women had the capability to run 26-plus miles. If I quit, everybody would say it was a publicity stunt. If I quit, it would set women’s sports back, way back, instead of forward. If I quit, I’d never run Boston. If I quit, Jock Semple and all those like him would win. My fear and humiliation turned to anger.”

The attention of the press truck was on her yet again, but the excitement had since faded, replaced with accusations of “'What are you trying to prove?'” and “'When are you going to quit?'”.

She had laced up that morning with no agenda except to run. But now for Kathrine giving up wasn’t an option and these accusations only hardened her resolve to fight to the end. There was more than herself that was at stake.

She recalls saying to Briggs, “… no matter what, I have to finish this race. Even if you can’t, I have to—even on my hands and knees. If I don’t finish, people will say women can’t do it, and they will say I was just doing this for the publicity or something. So you need to do whatever you want to do, but I’m finishing.”

Crossing the finish line was the goal, not speed, so the team fell back into a slower pace, and Kathrine did her best to flow into a rhythm despite the cold, bitter air adding misery to her already rattled mind and body. One of her hands was bare, the frosty air settling on her skin as Semple had failed to rip off her bib number but had successfully torn off a glove.

“My left hand was wet and freezing; losing that glove was bad because if your hands are cold, you are miserable all over.”

Miller caught Kathrine off guard, angrily voicing his concerns that his ambition of becoming an Olympic competitor in hammer throw was now ruined, with the events prior scarring his reputation.

“We were just falling into the rhythm of Arnie’s stride and beginning to relax when Tom, still fuming, turned to me and blurted out, 'You’re getting me into all kinds of trouble!'”

"Tom ripped the numbers off the front and back of his sweatshirt, tore them up and threw them to the pavement, and shouted, 'I am never going to make the Olympic team and it’s all your fault!'"

With a painful stab to Kathrine's pride, “…you run too slow anyway,” he powered ahead, abandoning his team.

Kathrine’s self-esteem was shaken, but Arnie helped her stay on task, “’Let him go. Just let him go. Forget it, shake it off!’”

Kathrine was overwhelmed with embarrassment and fatigue – but she kept running.

“I kept my head down, I didn’t want to see anyone, as this was the only way I could lick my wounds in public”.

Eventually, Kathrine, Briggs and Leonard overtook Miller – but she couldn’t wait for him. She had to keep momentum.

As she put one foot in front of the other, conquering more miles, she felt the fog of fatigue disperse, and was uplifted by the energy of the crowd.

“The distance, as it always does, gave me time to think and dissipated my anger… My thinking rolled on: The reason there are no intercollegiate sports for women at big universities, no scholarships, prize money, or any races longer than 800 metres is because women don’t have the opportunities to prove they want those things. If they could just take part, they’d feel the power and accomplishment and the situation would change. After what happened today, I felt responsible to create those opportunities. I felt elated, like I’d made a great discovery. In fact, I had.”

Pain had settled in, her feet burdened with "big blisters... that would soon burst," but lost in this hard-earned insight, Kathrine didn’t even notice she had triumphed over the famous Heartbreak Hill – one of Boston Marathon’s most daunting challenges for runners.

She recalls her conversation with Briggs;

“’...you passed over Heartbreak a long time ago!’”

“’We did? Gosh, I missed it. Why didn’t you tell us?’ I actually felt disappointed; I thought there would be a trumpet herald or something at the top.”

With feet "bloody" and blistered, Kathrine Switzer crossed the finish line at 4 hours and 20 minutes – but it wouldn’t be for the last time.

Kathrine Switzer: Beyond The 1967 Boston Marathon

Kathrine Switzer’s journey demonstrated that it was the limitation of social thinking rather than the physical and mental capabilities of women that was a true barrier. Since that life-changing race, Kathrine has committed her life to growing opportunities for women in sport… because with opportunity comes the foundations of equity.

With the shocking incident published in newspapers, her face and name were suddenly recognised across the globe. Kathrine had laid the foundations of a running revolution – and with this accidental fame she continued to champion women’s rights including the right to officially compete in endurance races.

By 1972, five years after she crossed the finish line with bloody feet and a mission for change, women were officially accepted into the Boston Marathon. She had even convinced Semple that women were serious runners – and they were here to stay.

Alongside her fight to evolve archaic perceptions of gender and to nurture a world where women are supported, encouraged and celebrated in their athletic endeavours, she continued pursuing her own running goals and became a marathon veteran.

In 1974 she competed in the New York City Marathon and won, and in 1975 she crushed her Boston Marathon personal best – finishing at a time of 2:51 and ranking 6th globally.

Kathrine is also the founder of 261 Fearless – a global organisation that actively creates opportunities, educates and inspires women to embrace the physical and mental health benefits of running. Every woman deserves to feel fearless and empowered. 261 Fearless provides that network of support in a safe, non-judgmental environment. It unifies women across the globe to achieve their athletic goals, build confidence and grow self-esteem.

50 years after the race that changed Kathrine’s life and the lives of women across the globe for generations to come, she wore her race number 261 one more time. She participated in the 2017 Boston Marathon, commemorating the historic race and crossing the finishing line at 4 hours and 44 minutes – adding just 24 minutes to her race time of half a century prior. At 70 years old she had proven in her lifetime that neither gender or age is a barrier. All that matters is that you run.

Today, Kathrine has run 41 marathons, is an inspirational public speaker and prolific writer. She is the author of 3 books; Running and Walking For Women Over 40, 26.2: Marathon Stories and Marathon Woman, which has been quoted throughout this article.

2023 International Women’s Day: Embrace Equity

Katherine never set out to be a hero. Nevertheless, her experience and integrity sparked change in the world to not only accept women in sport, but to encourage, support and inspire female athletes of all abilities and backgrounds.

However, the work isn’t done and as we move forward, together we can continue to strive for positive change.

The theme of the 2023 International Women’s Day is Embrace Equity. The terms equality and equity are frequently used interchangeably, but it’s important to know the difference.

Equality is the understanding that every individual or community has value – and regardless of gender, age, background or ethnicity, everyone deserves to feel safe and have access to the same opportunities and resources.

Equity takes this a step further. It’s the understanding that every individual or community has value but also has different needs and circumstances that should be catered for to ensure a positive outcome for each individual.

For example, in running terms equality would mean giving everyone the same pair of running shoes. The outcome is the same and yet, the quality of outcome differs based on the individual’s needs. One running shoe may be an ideal size for one runner, but be too small and cause blisters and injury for another.

Equality on the other hand would be giving each person a pair of running shoes that fits their specific foot type, foot size and comfort needs to run happy and without injury.

Everyone’s needs are different. Equity ensures resources and opportunities are catered to the individual and their unique circumstances – celebrating our differences and accommodating them whole-heartedly.

Check out Kathrine Switzer's website for more information on the journey of this inspirational female athlete and social activist.

For more information on how to promote positive change this International Women's Day and beyond, check out the International Women's Day website.